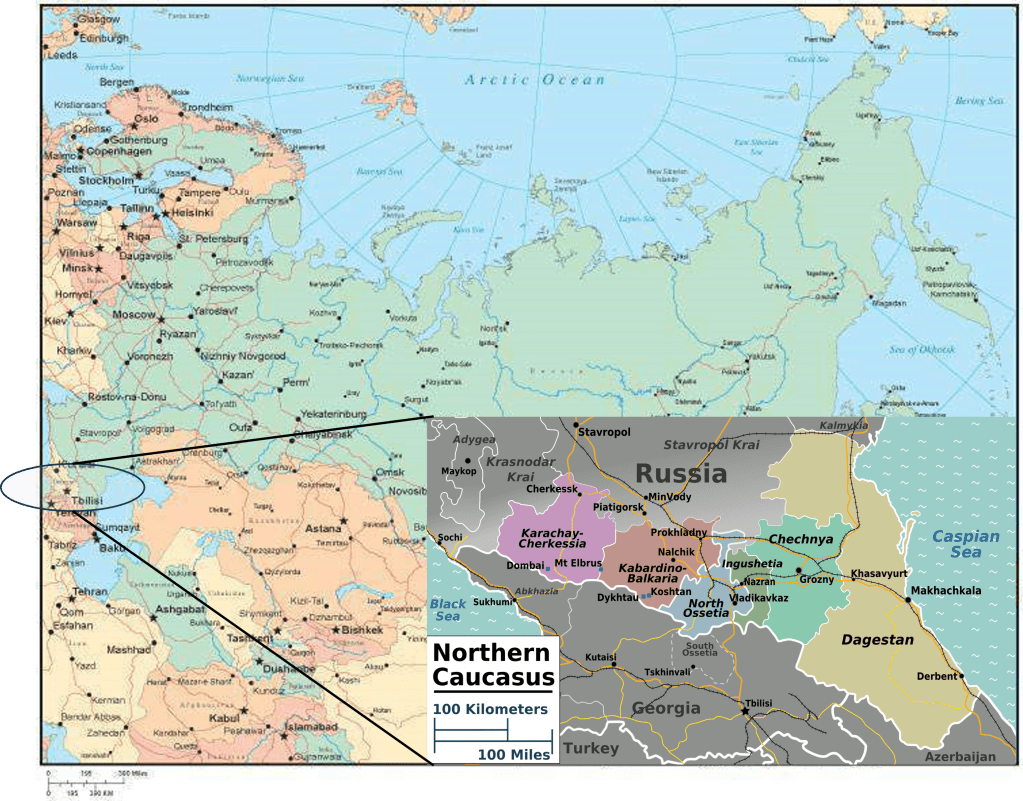

This post continues my exploration of the Russian Caucasus into the supposedly wild and exciting republics of North Ossetia, Ingushetia and Chechnya – a famously restless and troubled part of Russia. Here is a map to remind readers where these places are:

I made this trip using three different guides, one for each republic, and started in Vladikavkaz in North Ossetia. It was founded in 1784 as a Russian fortress controlling entry to a strategically important gorge, and its importance increased further when the Georgian Military Highway was built to link Russia to Georgia (then part of tsarist Russia’s growing empire) in 1799. As Russian influence extended south, Vladikavkaz became an important administrative and industrial centre. Today the city is pretty, relaxed provincial city backed by impressive mountains…..

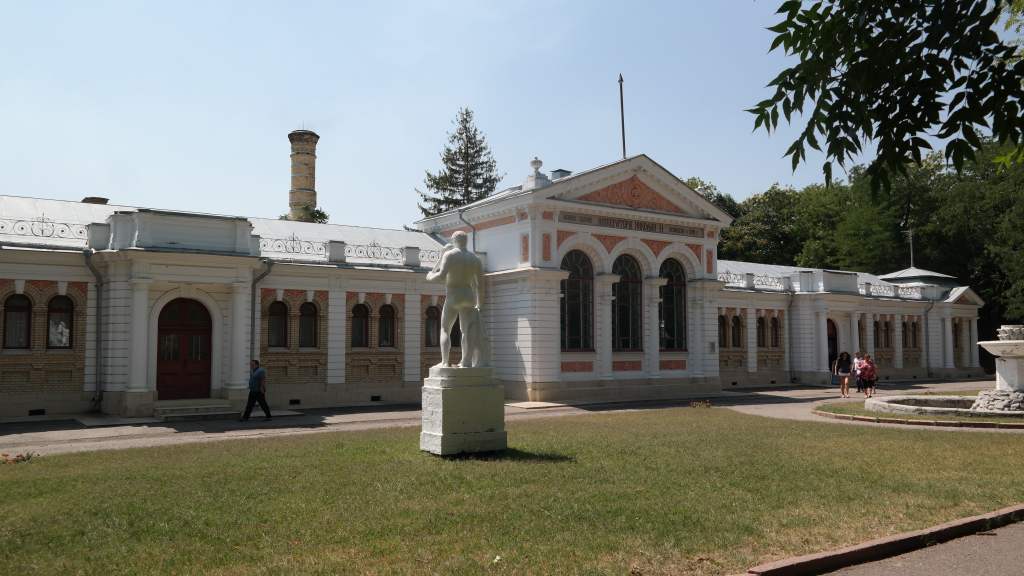

…..and has some grand old buildings.

During WWII the German army reached as far south as Ossetia in its quest to seize the Soviet oil-producing centre in Azerbaijan, but they were beaten back by the Red Army at Vladikavkaz after fierce fighting. A short way outside of the town is a large memorial to the heroes of this battle – including one soldier who threw himself across the opening of a German machine gun post to stop the enemy from being able to fire at his colleagues. My guide emphasised the heroic role of the Ossetian people in resisting the Nazis and said that the neighbouring Ingush and Chechens had not fought as bravely and were the source of the all the trouble in the region.

Vladikavkaz was interesting enough but would probably not have justified my trip in its own right, and after a day I was transferred to the border with Ingushetia to continue my trip and meet my next guide. The border post was intimidating, with armed guards, and I needed a special permit to get through.

Here, the vibe suddenly became very different. The landscape changed from pleasant, forested valleys to wild, empty mountains; instead of churches there were mosques; and the few local people looked at us suspiciously.

The countryside was sprinkled with small empty villages, each having several defensive towers.

Our guide explained how the villagers would take refuge in these structures when threatened by bandits – something which must have happened very often. He also said that the Ingush had indeed fought heroically in the Red Army but their role in WWII was not much mentioned by the authorities because they were Muslim. Instead, their reward was to be forcibly shipped off on Stalin’s orders to even more remote parts of the Soviet empire to create new settlements in places like Siberia or Kazakhstan – an often-unsuccessful experiment which led to them freezing or starving to death. Our guide clearly and understandably deeply disliked Stalin and claimed that he was in fact Ossetian, and not Georgian as is commonly believed. According to him, all the region’s problems were caused by the Ossetian and the Chechens.

Although somewhat intimidating, Ingushetia was a very beautiful and interesting place to visit, and I left regretting that I could not stay longer. I was driven to the border with Cheyna – a surprisingly relaxed crossing compared to the one between Ingushetia and Ossetia – to be met by my third guide, a Chechen.

Despite its fearsome reputation, based on the violence of this republic’s bloody 10-year struggle for independence and the alleged role of Chechen people in criminal activity in Russia, the capital city Grozny was a rather dull place. Almost completely rebuilt after the city was flattened in the war from 1999 to 2009, it boasted new skyscrapers, mosques and government buildings – as well as a history museum largely devoted to the cult of the current leader, Ramzan Kadyrov and his father (president before him until he was assassinated). Kadyrov rules the republic with an iron fist and is fiercely loyal to Russian president Putin and his pictures are everywhere. My guide avoided talking about the history of Chechnya or its current leaders but did say that in his view all of the region’s troubles were caused by the Ossetians and Ingush, and not the Chechens.

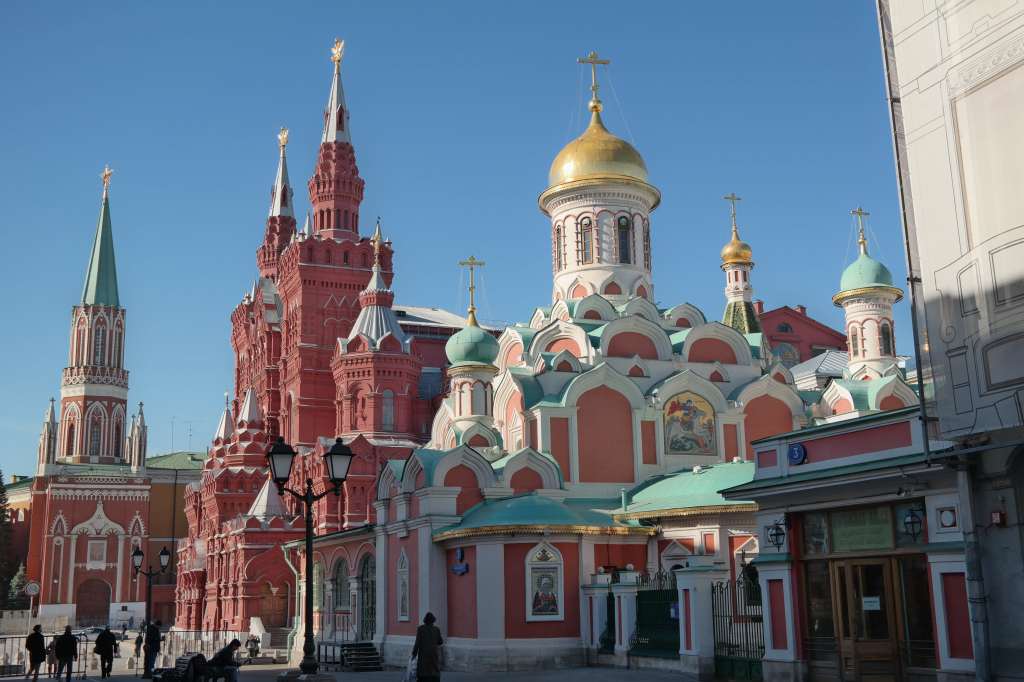

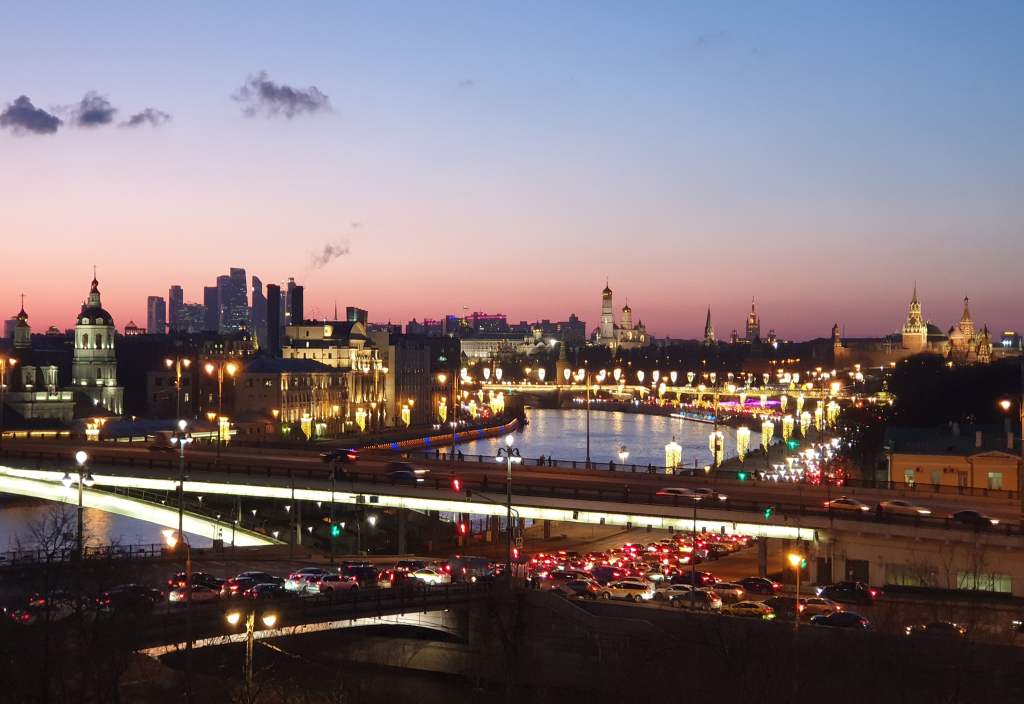

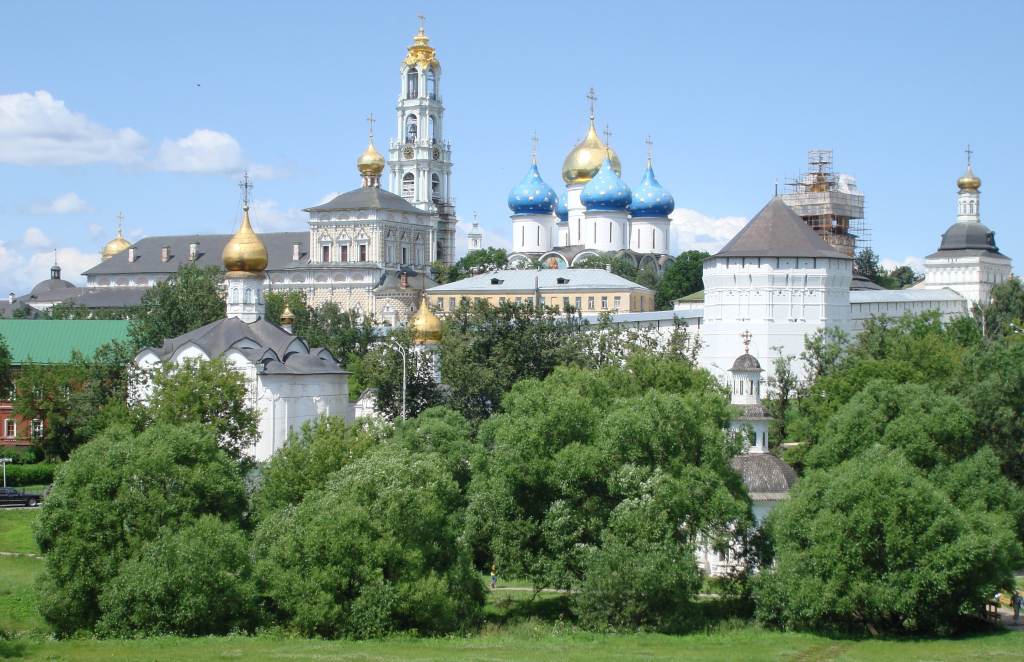

After a day wandering around looking at modern buildings, visiting the impressive main mosque and the bizarre history museum, I had seen enough and headed to the airport for my flight back to Moscow. It has been an interesting week seeing a part of Russia that very few tourists visit – not even Russian ones – and learning about the region’s troubled past. For me, Ingushetia was the most impressive of the three republics, despite a vague feeling of being unwelcome there, and I would like to go back one day to go walking in their wild mountains and visit more of their eerie, empty villages. In the region I also still have not visited the republic of Dagestan, which contains the city of Derbent (Russia’s most southerly city and probably its oldest) and its fort, dating from the times of the Persian Empire (6th century BC).

Previous Post: The Russian Caucasus part 1