Today I had one of these long drives that had become typical of my holiday in Namibia – from Luderitz in the southwest corner to Fish River Canyon, in the south. There was a direct – and rather dull looking – main road that could take me most of the way there. But since I had already travelled part of this, I decided on a detour around the southernmost part of the country, the border with South Africa.

Shortly after Luderitz, I had a pleasant surprise – on either side of the road was a carpet of flowers. They are only visible in the morning, and close during the afternoon sun, so I had missed them on the way here. They stretched away in all directions as far as the eye could see.

I stopped for a very good coffee at a town called Aus and decided to fill up on fuel. It was a lucky decision, since the station at the next town, Rosh Pinah – some 170km away – had run out of diesel. Rosh Pinah is a major centre for Namibia’s mining industry, and well off the main tourists routes. It had a similar feel to Luderitz, with many unoccupied people lounging around on the streets and looking at me with curiosity.

From Rosh Pinah the road headed east, following the Orange River, which marks the border with South Africa. It was dry season and the river was low, but it was still the first running water I had seen during all my time in Namibia. The road was empty, and passed some nice scenery (green for a change!) and a few shuttered camps offering kayaking excursions.

After enjoying the scenery along the river, I arrived at a huge vineyard just outside the town of Aussenkehr.

I had been on the road for six hours, and was tired. I ventured into the town in search of coffee but could only find a big branch of Spar where I bought a Red Bull. Most of Aussenkehr was a shanty town consisting of small shacks made of corrugated iron, and again groups of people hung around the shopping area and stared at me. At this place far from the tourist route, I had discovered the reality of Namibia for the majority of its people, and it’s a good time to talk a bit about the country and its history.

Before the Europeans arrived, Namibia was a typical African country settled by many different tribes – such as the Herero and the Nama – each with their own language and culture. They scraped an existence by farming or hunting in the country’s harsh, dry environment.

The country was largely ignored by colonial powers until the late 19th century – from the sea, the Namibian deserts looked inhospitable and unpromising territories. Then in 1883, the German trader Adolf Luderitz bought an area in the southwest of the country (around the city that bears his name today) from a Nama chief. He then persuaded chancellor von Bismark to declare Namibia a German territory. Colonial rule of Namibia was particularly brutal, even by the standards of the time, and culminated in what was possibly the world’s first attempted genocide (of the Nama and Herero peoples).

During the First World War, South Africa (allied to Britain) conquered the German colony of Namibia and proceeded to “administer” it – in practice, exploiting the country’s resources and its people. Eventually international pressure, UN resolutions and an armed struggle persuaded South Africa to grant Namibia independence – but only in 1990. Since then, the young country has done better than many other African countries, remaining a stable democracy and slowly addressing its many problems.

One of the most pressing issues facing Namibia is unemployment, which is around 20%. This is why there were so many people hanging around Namibian towns like Luderitz with nothing to do. Another problem is huge inequality and widespread poverty – many people are very poor, and live in shanty towns like the one at Aussenkehr. On the usual tourist circuit, visitors are insulated from the reality of life in Namibia for many of its people. You go from one nice lodge to the next, eat good food and drink good wine.

From Aussenkehr the road headed north across an especially featureless landscape, devoid even of plants.

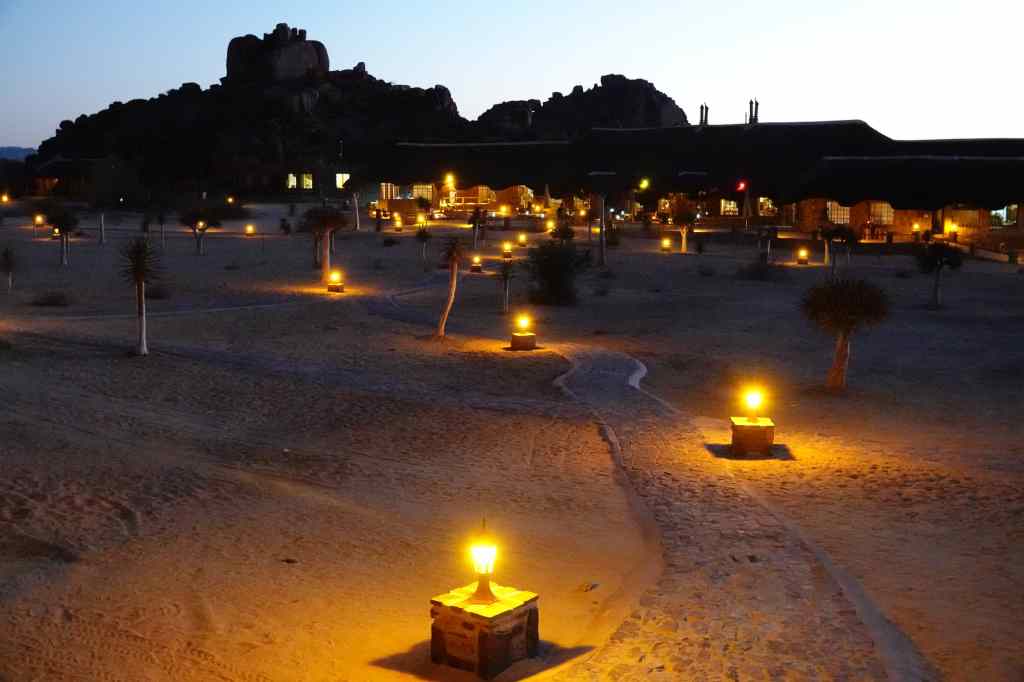

The landscape had a certain barren beauty, and further north, hinted at the spectacular Fish River Canyon that lay just out of sight behind the mountains – which I would see the next day. But I was tired, and after eight hours on the road, I was relieved to arrive at my destination – yet another stylish tourist lodge. I had found my excursion around the far south of Namibia and my brush with real life interesting, but was glad to be back on the comfortable tourist circuit.

Next Post: Fish River Canyon

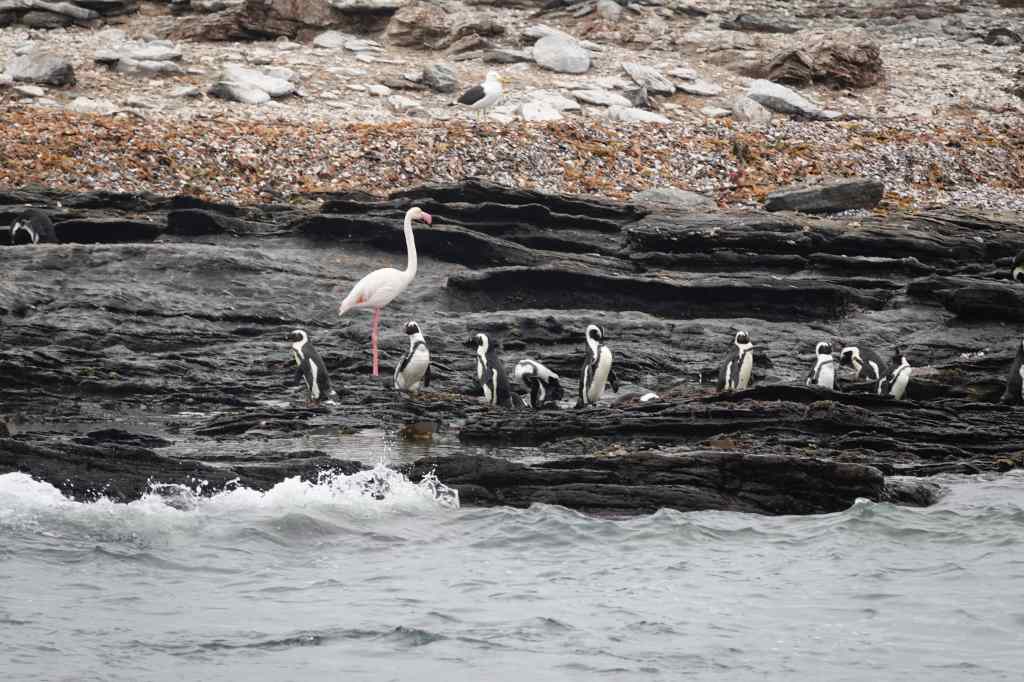

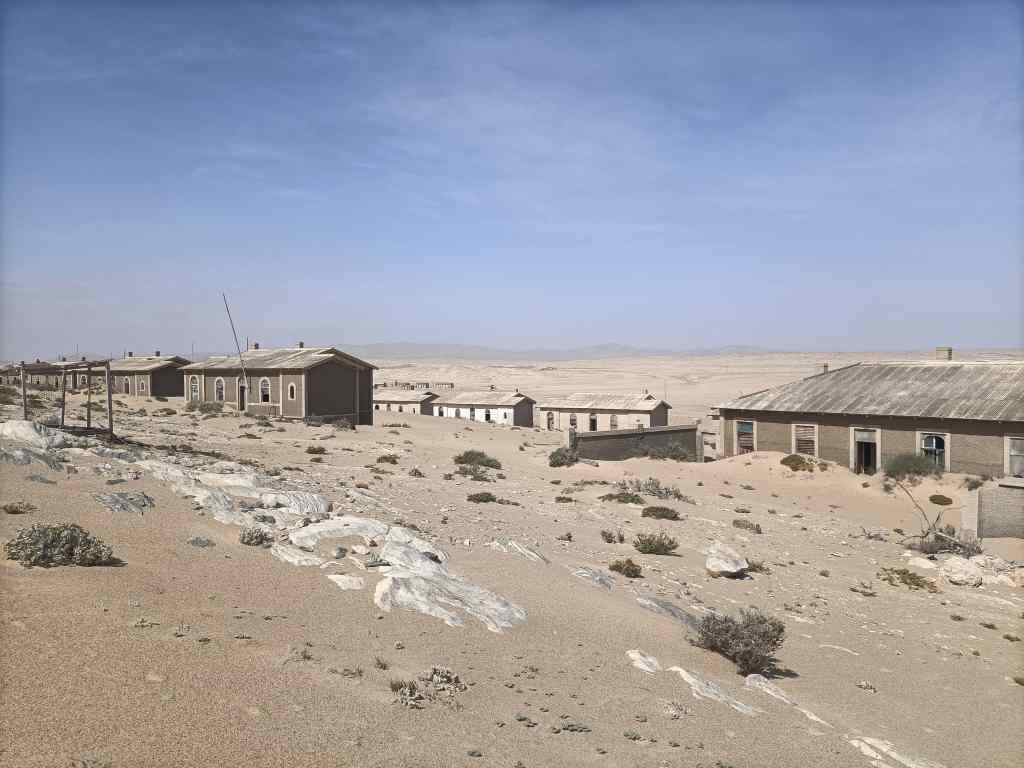

Previous Post: Luderitz, Kolmanskop and Halifax Island